The evolution of learning

To be fair, no one really knows where to go on the first day. But most people at least have a room number. Independent Research in Science was something I’d signed up for, but besides that it was mostly a mystery. I started out on the first day of school not even knowing what class to go to, because they hadn’t assigned me one yet.

I ended up with Honors Chemistry teacher Robert Becker as my IRIS supervisor. I was glad he was my mentor, because that meant I’d be spending two classes a day in the same place. I got started by looking up “latest research STL,” just trying to find a project I could assist with in the area. You don’t want to spend all day researching something you can’t join in on.

This was not the greatest choice. Everything I found was already published, obviously, so most people weren’t actually working on the study that I found interesting. That’s okay, though, because I then switched to looking up a university, like UMSL, and “newsroom.” This is where universities like to brag, which includes research papers that have just been published.

Some of the stuff I found was not science-related at all, but I ended up making a list of a few different studies I thought were cool, like a project that would help treat sickle cell disease. I figured I was done looking and should start narrowing down my choices, but Mr. Becker told me to spend one more class looking.

It was that next day that I found “Evolution of Learning”, a study lead by Aimee Dunlap, assistant professor of biology at UMSL. I was blown away. Aimee was going to be manipulating the evolution of flies, teaching them to make their most important decisions (such as where to lay eggs) one way even though they should be doing the other. This is cool, because you can see whether a fly goes with what it’s taught, or with it’s instinct, which is wrong.

So, I emailed her. Well, to be fair, I wrote an email I tweaked and edited and panicked about for two days, and then I emailed her. I got a great response; she let me come into the lab and gave me a project to work on.

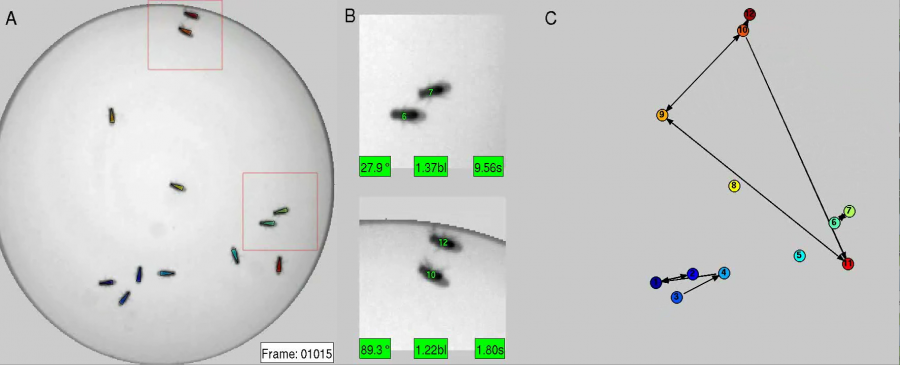

This is how it works. Take 12 flies, paint them different colors to identify them, and put them in a round dish. Then film them moving around for an hour. Then, go back and watch the video 12 times, watching a different fly each time. Every time the fly “interacts” with another fly, you have to write it down. It sounds super monotonous, but by the time you’re done, you can find out the way flies relate to each other.

Aimee’s theory is flies relate in the same way dolphins do, and by relation, similarly to humans. It’s really strange, because the flies I’m working with, Drosophila melanogaster,or fruit flies, only live for about a month, so how can one hour of interaction be the same as a century?

More updates as I move on, plus an extra exciting, squishy robot.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Kirkwood High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Grade: 11

Twitter handle: @chloe_e_king

If you could be another Call staffer, who would you be?: Julia Wunning-Zimmer

Interests: Harry Potter, Star...

Grade: 12

Twitter handle: N/A

If you could be another Call staffer, who would you be?: Brian Goyda: because, it's Brian Goyda.

Interests: Art, Cooking,...