Gauging the gap

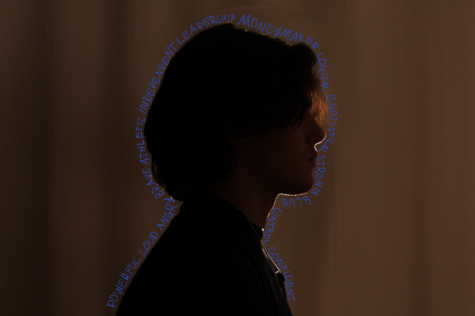

Samaya Trawick, Junior, raises her hand in math class to ask a question.

As the deafening noise of the halftime buzzer sounds, Samaya Trawick, junior and varsity cheerleader, leaps into place before her team begins their routine.

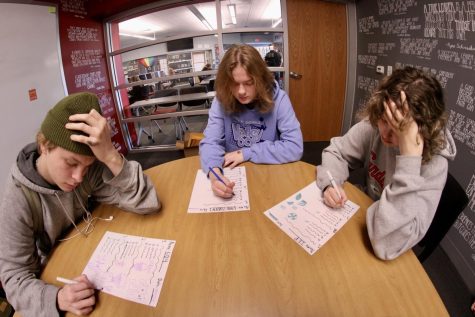

At this moment, she feels a part of something. But for Trawick, that is not always the case at KHS. Taking both AP and honors courses over the last three years, Trawick is an exception. With only 22 percent of African-American students enrolled in AP and honors classes during the 2017-2018 school year, Trawick said the lack of diversity in an advanced classroom setting is a problem.

“In my AP Lang class there are only three black students including me,” Trawick said. “There are a lot of students in that class for there to only be three of us. Even though there are some [black students], I feel like there definitely could be more.”

Sixty-nine percent of African-American students passed their AP exams during the 2017-2018 school year (31/45) while 90 percent of white students did (811/901).. But the separation does not stop there. Trawick said the divide among students is prevalent in aspects other than academics. In the halls, at lunch and after school, she says the gap is clear.

“If you walk into the cafeteria during lunch, you will see all of the black students sitting with the black students and the white students sitting with the white students,” Trawick said. “If you’re black and sitting with the white students, then you’re seen as not black enough to sit with the black students.”

What differs for Trawick is that her friend group at KHS is mostly white. She said hanging out with white people often causes her peers to look at her differently. She remembers once in middle school being called an “Oreo.”

“You’re black on the outside, but white on the inside,” one of Trawick’s peers told her. “I was confused because I thought I was friends with everyone.”

Keziah Smith, freshman, feels as if she stands out too. Throughout her day, she follows a schedule with classes of little to no other African-American students.

“In my English class there is a huge gap,” Smith said. “I’m the only African-American. In physics there is only one other, and in many of my other classes there’s maybe a few more.”

Smith said teachers who place students in categories such as “the rowdy kids” or “the leaders” play a large role in causing students to feel like they can’t reach their full potential. She said peers also make assumptions about each other and contribute to the achievement gap.

“Everytime you go somewhere and [people say] ‘you’re not worthy’ or ‘you’re not smart enough for that class,’ you’ll start to believe it,” Smith said. “It will turn into a cycle of feeling like you can’t talk to anyone.”

Smith, like Trawick, has several close friends of different races. And while in the past she has felt used, mentioning that she was seen as their “token black friend,” her relationship between her race and friendships is becoming more positive.

“The friends I’m with now are more open,” Smith said. “They feel comfortable talking about race. There’s never that awkwardness. They never ignore that I’m black, but they don’t find it to be a personality trait.”

The feeling of being able to connect is huge for Smith, especially in the classroom. According to Smith, having teachers who have something in common with their students can make them feel more comfortable to go to the teacher for help.

In my English class there is a huge gap; I’m the only African-American.

— Samaya Trawick

“I’ve had two black teachers in my whole academic career in KSD,” Smith said. “But I know people that have not had a single one. If there was more representation in the staff, then students would feel better connected.”

According to Dr. Michele Condon, KSD superintendent, the current goal is for the district to see how the number of minority students in AP and honors classes reflect how many minority students there are in the school. Romona Miller, assistant principal, thinks a way to improve this would be if students begin to see themselves in their teachers.

“When you have role models in place who look like you, that is an encouraging factor,” Miller said. “That is empowering to any student to see someone who looks like them. It often provides a commonality of experiences for children, and it makes it easier for parents to come in and see someone who looks like them.”

With a hop in her step, she runs off the hardwood floor at the end of halftime. Surrounded by the rest of her team, she hopes for a solution to the achievement gap in the future.

“I think we should not necessarily stop thinking about the gap, but make a solution to fix it,” Trawick said. “I’m not sure what the solution could be because it is so ingrained in our heads. It is definitely going to take some time to get rid of it and create a bridge for both races.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Kirkwood High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

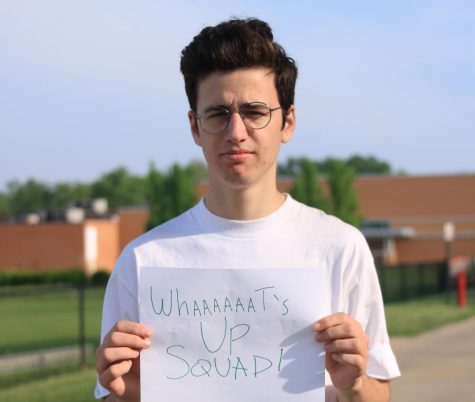

Interests: Playing tennis, traveling and watching Netflix.

Favorite musical artist: Billie Eillish.

Favorite quote:“Whenever I’m about to do...

Interests: I throughly enjoy hiking and being outdoors, exploring urban areas, reading, procrastinating homework, hanging out with friends, theater, soccer,...

Interests: Takin’ pics.

Favorite musical artist: Billie Eilish.

Favorite quote: “I want people to be afraid of how much they love me.” -Michael...

![“[Fashion is] a means to express myself,” Ezra Birman, senior, said. “I can’t imagine a world where I didn’t dress like this.”

Art by Ally Hudson](https://www.thekirkwoodcall.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ezrapolaroid-e1646944084982-475x318.png)