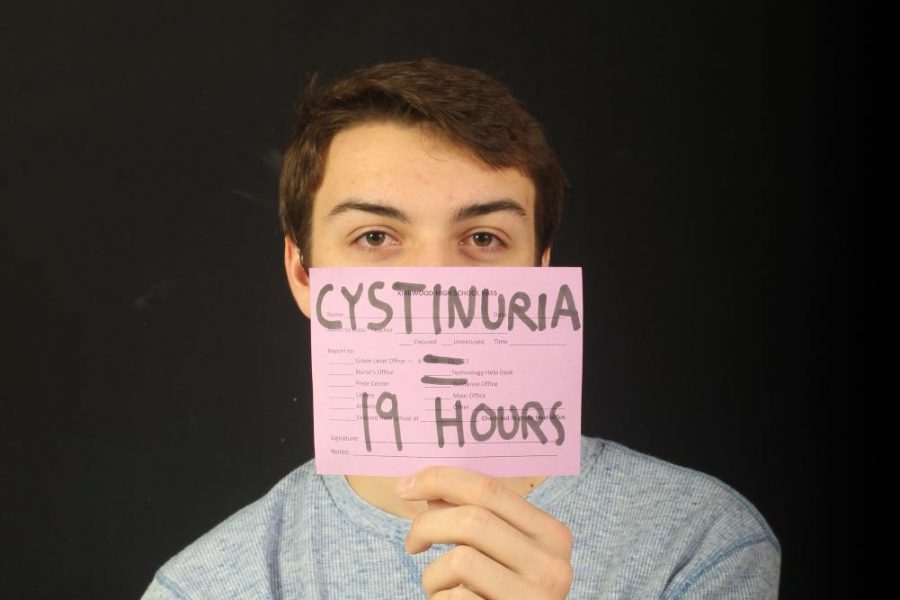

The top priority

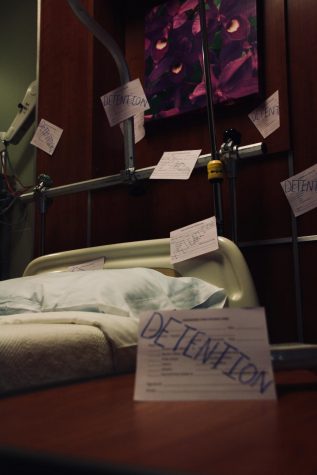

Aaron De Marco, senior, received 19 hours of detention due to missing 21 days of school after being diagnosed with cystinuria. “I felt like I was being targeted twice with the condition and the attendance policy,” De Marco said.

They drilled a hole in his back. They put metal tubes in his body. He came to school with a cane.

Then, under KHS’s revised attendance policy, he got detention.

Aaron De Marco, senior, has cystinuria, a rare and aggressive condition which causes him to produce kidney stones every single day. Symptoms include anything from sharp, intense pain in the lower back to constant stomach pain and blood in the urine. Not long after he was diagnosed in the fall of 2017, he found out he needed surgery. The first one lasted over six hours. Another came not long after. Then another. And another. Again and again, until he had been on the operating table eight times. When he came home from the hospital, he was unable to walk without support. He couldn’t lie down on one side

of his body. He couldn’t even go to the bathroom by himself.

“I was helpless,” Aaron said.

Aaron was absent for 21 consecutive school days in his first semester of junior year. That first day back, he walked into his seventh hour history class still using his cane for support. That’s when he got the slip from the principal’s office, which said Aaron had 19 hours of detention.

“I was pretty mad,” Aaron said. “Dealing with something that you’re in no way control of is already hard enough mentally. And on top of that, I felt like I was being targeted twice with the condition and the attendance policy.”

According to KHS’s revised attendance policy, “Illness of the student” is listed as the second of six options available for an excused absence. Regardless of whether or not the absence is excused, “no credit for the semester will be given students whose total absences exceed ten periods per class per semester without administrative approval.” However, the three-page policy also states: “Students will be granted the amount of time they were absent in which to make up work.” In other words, Aaron wouldn’t be dropped from his classes as long as he made up the hours he missed after hitting his eleventh absence.

Romona Miller, assistant principal, said for students in a situation like Aaron’s, the administration mandates the student make up the hours in some fashion, whether it be before or after school with a teacher, in the library or in detention. The student is given a log to turn in to their grade-level secretary that tracks their hours, and if they aren’t met by the end of the semester, the student is dropped from those classes with no credit and an F.

“It really should work in your favor that you have someone to help you get caught up in something you should be working on,” Miller said. “But for students who are having real medical issues, I don’t think [the attendance policy] has changed things that much.”

Carrie De Marco, Aaron’s mom, called Aaron’s grade level office every day he was absent. As Aaron’s illness continued keeping him out of school, Carrie said she began waiting for the inevitable attendance letter that, according to the policy, would be sent out to parents after certain numbers of days missed. She waited for something, anything, that would tell her what Aaron needed to do next.

The letter never came.

“Never, ever did they say [when I called] ‘You’ve missed too much school,’” Carrie said. “Never, ever did they reach out to me to say ‘Let’s make a plan.’”

Carrie was also never made aware she had the option to attend an appeals hearing. Only after Aaron came back to school did she learn KHS administration meets on Tuesdays to hear cases of students with over 10 absences. She had to schedule a meeting with Miller on her own time.

“What this process showed me is that the school would rather have your child sick at school than miss school,” Carrie said. “They want you to be at school, but at what expense?”

Miller said it is not possible for students to not receive communication from the administration during the process. While Dr. Michael Havener, principal, said he and other administration members are unable to comment on individual cases, he clarified for students in these situations there are multiple times when parents should be notified in relation to absences, through both a letter and phone calls.

“We’re very flexible,” Havener said. “The goal is not to punish. The goal is to help and support them as they try and make up the work. But missing 11 days is a lot, even when you’re sick.”

The goal is not to punish. The goal is to help and support them as they try and make up the work. — Dr. Michael Havener

To the administration, the results of the revised policy speak for themselves. Jessica Vehlewald, assistant principal, said from the 2016-2017 to the 2017-2018 school year, the number of disciplinary write-ups decreased by over 1,000, going from 2,541 to 1,521 the year after the policy went into effect. She also said so far this year, the numbers have been even lower.

“Now, we’re more free to do things that we just couldn’t under the old policy,” Miller said. “I think the students are to be applauded because they have risen to the occasion, and they’ve worked with this policy.”

Grace Hartman, senior, has gone through similar experiences in dealing with medical conditions under the policy. In March of 2017, Hartman was diagnosed with Wegener’s disease, a rare, brutal autoimmune disease which causes inflammation in blood vessels and can result in organ failure. She hardly ever slept, she said, and the school day became more and more painful. Eventually, the absences started to pile up.

“Luckily, that year, the attendance policy was not yet in place, or I would have been in a whole bunch of trouble,” Hartman said.

Her disease is chronic, so she said she is affected by it every day. She never knows when she’ll have a flare up, and therefore never knows when she will need to miss school to get treatment. Because Hartman is still dealing with her illness, she said she has had two different experiences: one before the policy, and one after. Once it was enacted, things for Hartman quickly got a lot worse, she said. Like Aaron, she eventually reached the 11th absence. Like Aaron, she said the process was very disorganized. Like Aaron, her parents were never contacted by the school. Her guidance counselor also never showed up to her appeals meeting.

“I’ve had to go out of my way,” Hartman said. “I feel as though there has been no communication, and no real plan set in stone for people in special circumstances. It seems like they don’t know how to handle it.”

After her appeals hearing, Hartman received a log to track the hours she was making up. Before school, after school, skipping dance practices, any way she could. After going through the process over multiple semesters, Hartman said making up over 120 periods a semester has taken over her life. She also said she’s felt intense pressure to make it to school even when her body is telling her not to. Even when she feels like she can’t breathe. Even when she thinks she’s about to pass out.

“I’m doing everything [the school] has asked me to do,” Hartman said, voice breaking. “[There were times] I would be thinking, ‘I can’t miss anymore school. I’ve already missed so much.’ I was pushing myself even when I probably shouldn’t have. So I’ve definitely felt I’ve had to prioritize my school life over my health.”

I was pushing myself even when I probably shouldn’t have. So I’ve definitely felt I’ve had to prioritize my school life over my health. — Grace Hartman

While Aaron and Hartman both described their experiences as overwhelmingly negative ones, this has not always been the case for students in similar circumstances. Joe Howard, senior, described the administration as incredibly accommodating and understanding. After being diagnosed with viral myocarditis, a disease causing inflammation in the heart muscle and spending eight consecutive days in the hospital, Howard returned to an administration ready to help him make a plan for the remainder of the semester. They even gave him a parking pass to allow him to park closer to his classes. And yet the theme emphasized over and over by all three of these students was that the process under this policy is nothing if not inconsistent.

“Our grade level principals talk [to each other] a lot about notification and things like that to make sure they are consistent,” Havener said. “And the actual attendance hearing is run the exact same way for all grade levels.”

In thinking about potential solutions to the problem, Aaron said he wants to urge the administration to revisit the policy with these cases in mind. To him, the policy fails to differentiate between a student with a medical condition like himself and someone who just decided to sleep in. And when asked if they believed the attendance policy has worsened what have already been for them stressful and difficult situations, Aaron and Hartman both gave an emphatic, frustrated, one-word response.

Absolutely.

“The focus needs to be on treating students the way they need to be treated after something like this happens,” Aaron said, his hands clenched tightly in his lap. “And I feel like the policy really targets people who don’t need to be targeted. Because [under the policy], I think I was mistreated. I think I was denied basic respect.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Kirkwood High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Interests: I try to write something new every day, and read a new book every week. Classical music is >>>>>> everything. I play piano,...