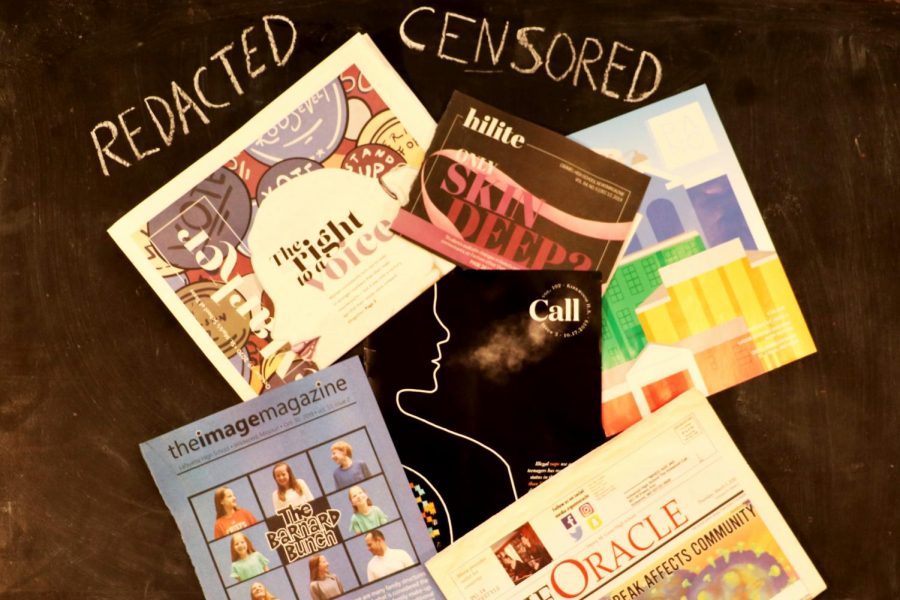

In-depth: Speaking out around St. Louis

The Supreme Court case Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier allows school administrators to have prior review and restraint on student publications. Now, there is no universal standard protecting the rights of a school newspaper in the United States.

Teen pregnancy, divorce, tattoos. Each of these topics have been censored at a school within 40 minutes of KHS.

The Supreme Court case Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier allows school administrators to have prior review and restraint on student publications. Now, there is no universal standard protecting the rights of a school newspaper in the United States. However, New Voices laws, begun by a student-led initiative aiming to protect student press freedoms, have been passed in 14 states, counteracting the 1988 Supreme Court decision and extending First Amendment freedoms to the student press. KHS is a First Amendment school by practice, not policy.

Though a New Voices bill has not been passed in Missouri, many school districts have policies that extend the First Amendment to student-led publications. According to Nancy Smith, journalism adviser at Lafayette High School, the Rockwood School District has a policy in place that eliminates prior review and restraint. This means that school administrators cannot preview material before it is published and withhold it.

“This is a building where [the] student voice is respected by our administrators and it’s heard, and I think that is really vital for students to know and to appreciate and to also utilize,” Smith said. “To know that their opinions, and how they’re feeling and what they’re thinking is being heard and that they do have that right to use that voice in a responsible manner – it’s not always like that.”

This is a building where [the] student voice is respected by our administrators and it’s heard

— Nancy Smith

Like Rockwood, the School District of Clayton also has a policy that protects student press from prior review and censorship. Erin Sucher-O’Grady, journalism adviser at Clayton High School, said the district’s policy was put into place after a former principal attempted to censor the yearbook.

“I think that bringing back trust [of journalism] has to start on that local level,” Sucher-O’Grady said. “It’s not like there’s a reporter from the Post Dispatch that’s going to your school board meeting, paying attention to the decisions that are being made that are most closely going to affect our lives. We as a culture are now reliant on local journalism being student journalism, whether that’s at the high school or collegiate level.”

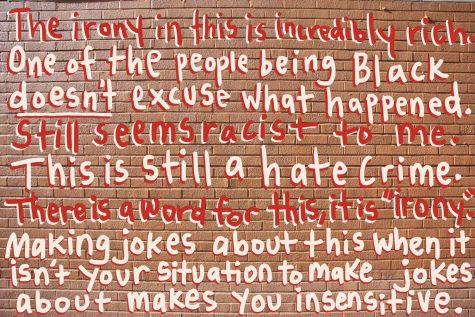

In Missouri, some schools are still subject to prior review and censorship by administrators. In 2009, Wentzville’s Timberland High School newspaper, the Wolf’s Howl, was blocked from distribution due to a picture of a student’s cancer ribbon tattoo. According to the Student Press Law Center, Timberland’s principal Winston Rogers said the spread violated the school’s “zero tolerance tattoo policy.” Nikki McGee, Editor-in-chief of the Wolf’s Howl at the time, said that schools are good places to have thought-provoking conversation, which is hindered by administrators limiting what students can and cannot talk about.

“The chilling effect is when you write something and you’re somehow censored against it, [and that] gives you a hesitance to report on certain issues in the future,” McGee said. “So maybe you think ‘we need to talk about this or cover this topic,’ but you remember your last experience, and you [decide] ‘you know what, no, we should avoid that.’ It’s almost like you’re scared to talk about [the issue] or you’re worried about backfire from your administration, and it really ends up limiting what you feel free to talk about. That chill effect is very scary and very real for student journalists, especially if they are still following prior review.”

Smith said that school officials respecting the student voice is vital, and not just for students on a publication. While students may learn their First Amendment rights in school, Smith said that many people today do not realize the relevance and consequences of their freedom of speech.

That chill effect is very scary and very real for student journalists, especially if they are still following prior review

— Nikki McGee

“You see so much of the news where it’s clear people don’t understand what the freedom of speech means,” Smith said. “They don’t get it.”

Because of this, Smith said it is important to have conversations about the freedom of speech in real-time and in school. Sucher-O’Grady also sees it from an educational standpoint. She said the higher and realer the stakes are, the better the student journalism will be.

“There’s no richer way to teach something than having people actually do it, and having those consequences be real life,” Sucher-O’Grady said. “Students rise to the occasion. When they know their work is going to be consumed not only just by their school building but the wider community and they’re going to hear about it from their parents’ friends, or a school board member, or the superintendent – the people that have power and influence are reading their work and making decisions with their words in mind sometimes. That is tremendously powerful and tremendously motivating.”

While other area high schools have policies similar to Rockwood and Clayton, many others – like Wentzville – do not have the same freedoms. Smith and Sucher-O’Grady hope to see this change.

“When have you ever seen an administrator step onto a basketball court and start calling plays,” Smith said. “If your basketball team is 0-10, is your principal going to start coaching the basketball team or start running practices? Of course not. If your marching band doesn’t win competitions, is your principal going to make a new playlist for them? Of course not. There’s no other area in the school where the court has said you have permission to step in and take control of that program.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Kirkwood High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

she/her

Hobbies and Interests: Playing/writing/listening to music, politics, exploring

Favorite Song: “Bad (Live)” by U2

Favorite Quote: “Life...

she/her

Hobbies and Interests: Photography, spending time with family and friends, hiking, traveling.

Favorite Song: "More Than A Woman" by the Bee...